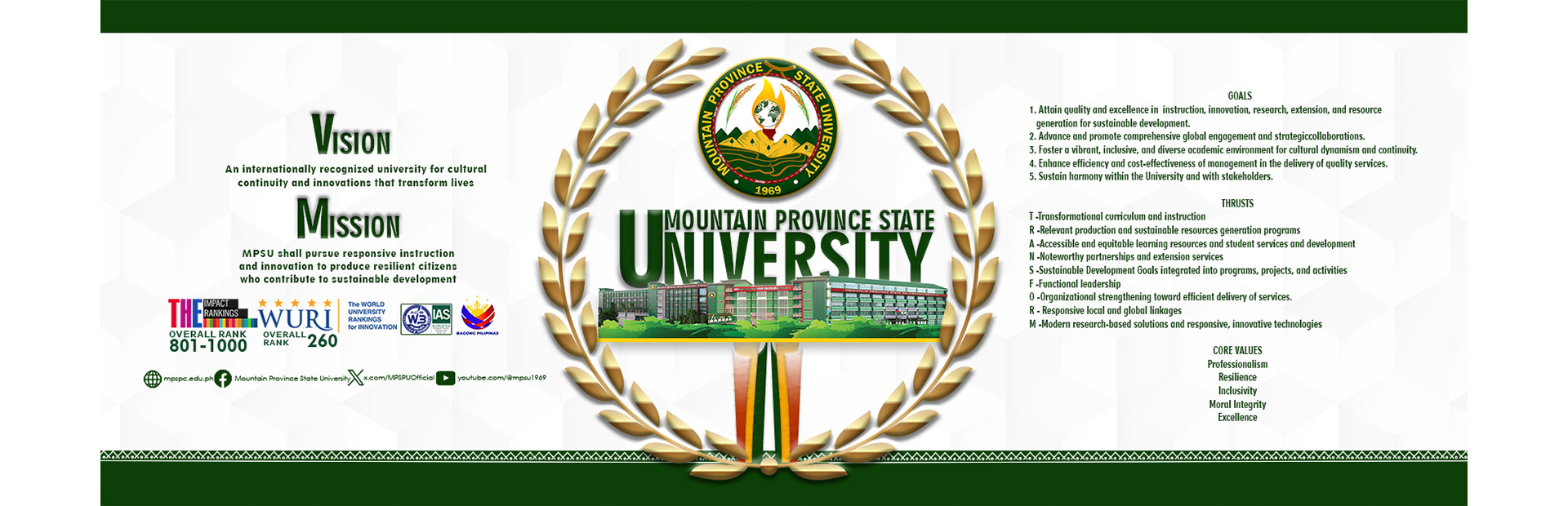

NEEDS-BASED COMMUNICATIVE TASKS IN SPEAKING ENGLISH OF MPSPC BONTOC CAMPUS FRESHMEN

Johnny P. Cayabas, Jr.

Introduction

English has become so widespread that it is now spoken either as a native language or as a second language in most of the countries around the world including the Philippines. In fact, Asiaweek (1999) claimed that our country has the third largest number of English speakers in the world, surpassed only by the United States and Great Britain. Filipinos have become “functionally native speakers” of English; they use English in what linguistics calls “domains of function and social penetration.”

At present however, there is a slow but serious decline in the English proficiency of Filipinos. This is ironic given that the Philippines once boasted, with some justification, of being the world’s third largest Anglophone country.

Some think that the decline has more general causes. As the economy has underperformed, so has education. About 43 percent of students finish high school and only 2 percent finish college. Moreover, a Department of Education study in 2004 showed that only 1 in 5 in public high school teachers was proficient in English.

Long-term foreign residents say that in the late 1960s it was possible to converse in English with almost any Filipino that had attended elementary school.

The government recognizes the decline, which is widely bemoaned in the local media. In 2003 the government ordered the teaching of English as a second language in elementary schools and made it the medium of instruction for 70 percent of teaching in high schools. It has mandated remedial English classes for teachers (McLean, 2010).

It used to be that the Philippines’ biggest competitive advantage in the global job market is the proficiency of Filipino skilled workers in the English language. This advantage, however, is fast being eroded by the rising competition from other countries coupled with declining mastery of the English language by the country’s college graduates (Marcelo, 2010).

Many fresh graduates who are trying their luck in the Philippine call center industry go for interviews but they either go home unemployed because of poor English speaking skills.

Moreover, out of 100 applicants for call center positions, only less than five percent are hired because of inadequate English skills, according to the Business Processing Association of the Philippines (Tormes, 2008).

Though the Philippines remains to be the top nation in Asia when it comes to English speaking skills (and third around the world next to United States of America and United Kingdom), the fact remains that our English speaking skills are getting poorer, regardless of our ranking when it comes to the list of English speaking countries in the world.

While it is true that English is the medium of instruction in the Philippines, the country is presently equipped with Filipino teachers who have poor English speaking skills and most often than not most teachers revert back to their native dialect when teaching English (Magallanes, 2010).

To quote Russ Sandlin, an American businessman in the Philippines who recently closed his call center in Manila, said “not even 3 percent of the students who graduate college here are employable in call centers.”

To date, Andrew King, country director of International Development Plan (IDP) Education Philippines, recently revealed a seeming drop in Filipinos’ proficiency in English from the results of Filipino takers of the IELTS they administered in 2008.

In the IDP Education review of IELTS results they had administered in countries all over the world for 2008, he said that the Philippines’ average overall score was 6.69, which was below the 7 passing score of the Australian government. In their analysis of the results and the Philippines’ system of English instruction in schools, King said that the deteriorating level of English proficiency could be attributed to the deficiencies in the proficiency of the teachers teaching English as well as the poor quality of resources or textbooks being used in schools (Ronda, 2009).

However, Tenedero (2002) suggested that the poor quality of education in the country can be improved by constructing new educational methodologies, tools, and systems that can lead to holistic learning. The development of adequate and appropriate instructional materials will help facilitate learning process in the mastery of basic skills and help strengthen critical thinking skills.

In emphasizing the importance of developing the students’ ability to communicate in English in a target situation, Ang (1992) stressed that teachers need to look for ways of creating various forms of interaction that require frequent use of genuine and stimulating communication activities in the classroom. The teacher’s job is to provide the students opportunities to use the language for themselves: to say what they want to say rather than what they are directed to say.

Task-based materials provide such opportunities. They are anchored on four fundamental beliefs which communicative approach to language teaching holds regarding materials: materials in the classroom should be authentic, real and purposeful, contextualized, and must reflect the language needs of the learner (Murcia, 2006).

Communicative tasks provide the learners not only the opportunity to acquire the language but also to develop his skills needed for his different purposes. In addition, it provides venues for the students’ development of communicative competence in listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

Truly, teaching materials help and guide in the selection of content and the design of learning experiences. Process has primacy over product.

In MPSPC where the researcher is teaching, it was observed that English and even non-English instructors perennially complain on the students incapacity to express orally their ideas fluently and accurately in English. This language constraint has resulted to their poor language performance.